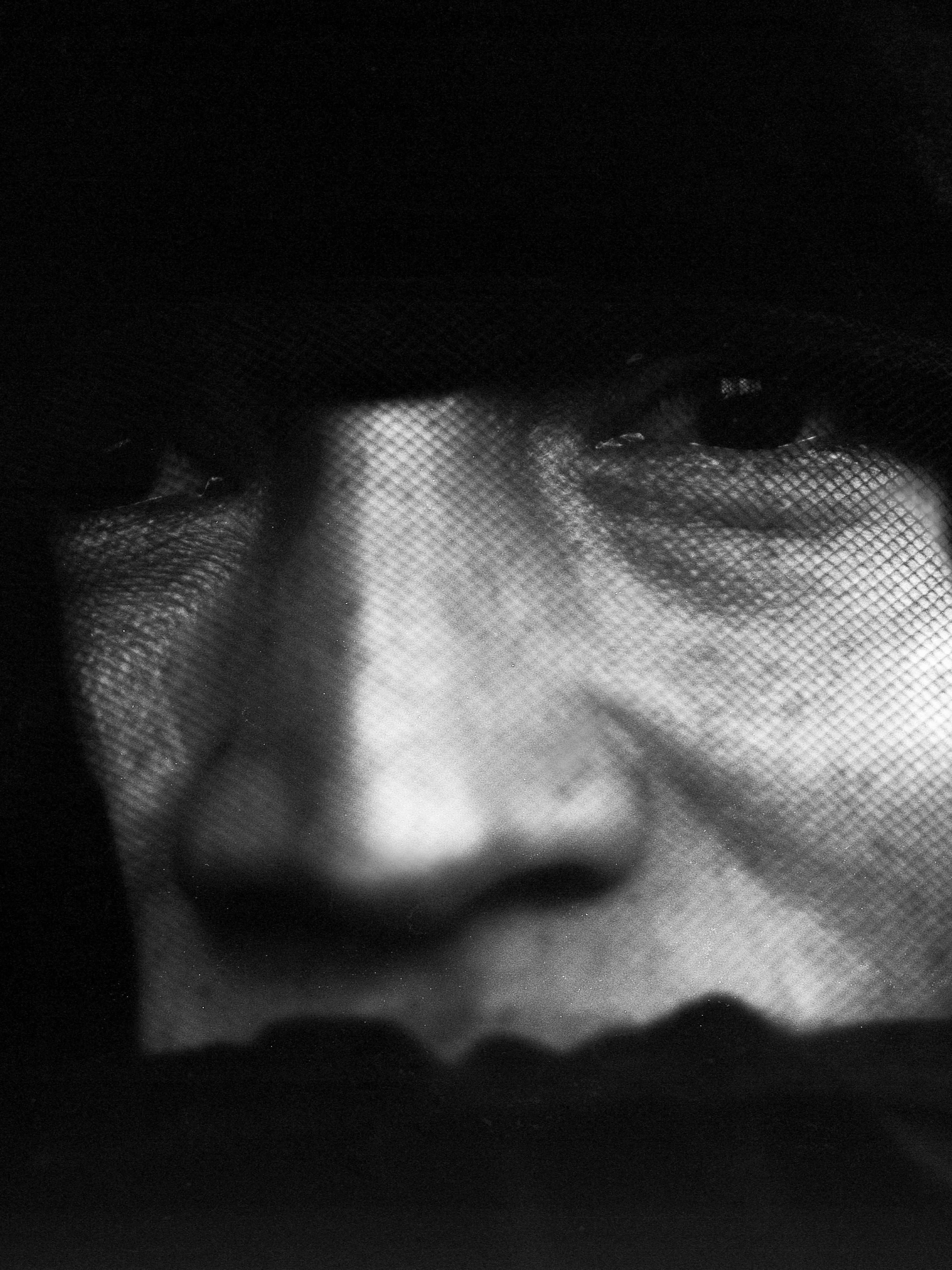

Transitioning to a woman, loosing male privilege.

“Since I was born, as far I can remember, I felt that I was a girl,” explains Lola Vásquez while sitting on a park bench in Jocotenango, Guatemala. “I referred to myself as a female. Obviously, I was scolded at home. Since I can remember, I’ve been a girl. Socially, it was imposed on me that I couldn’t be one; I was not allowed. At 33, I decided to transition.”

37-year old Lola Verónica Vásquez is now a stage actress known for her activism as a self-described spokesperson for the trans community in Guatemala, a group that faces several challenges in the tropical country. For instance, a census study conducted in 2015 found that 35% of trans women work in the sex industry where it is legal to offer sexual services, but it is illegal for customers to pay for them. That same study found that 61% of trans women don’t have an income above the local minimum wage (388 USD per month) while the cost of living according to Guatemala’s National Institute of Statistics is of 1063.41 USD per family of four.

There are around 4,840 trans women living in Guatemala, and 99% of those in a relationship are with a male partner. However, many of these relationships can be subject to domestic violence. Such was the case of Ms. Vásquez:

“When I transitioned into a woman, I was hoping I’d find a boyfriend. You know, what a normal Guatemalan girl wants: to be together with someone, to work and to live happily ever after. But, no. It didn’t happen that way,” she recalls. “On the contrary, I lived through violence with him.”

According to Ms. Vásquez, she was living the underside of the relationship experience she had hoped for: she was subjected to machismo. Her partner had a strong problem of drug and alcohol abuse, and he would often force her into submission via death threats with handguns and machetes. She eventually left him.

“What I wanted was a man, but thanks to all my fellow women, I learned about feminism,” Ms. Vásquez explains. “Now, if you tell me to submit to a man, I would never do I again.”

Trans people in Guatemala cannot legally choose their gender. There was a law initiative introduced on February 22, 2018 so that they would be able to do so, but it was eventually dismissed on August 31, 2018 by the Commission of Legislation and Constitutional Points, which is led by Fernando Linares Beltranena, a far-right congressman, and several other rightwing legislators who control the commission.

On top of that, an older law initiative with several points that would be detrimental to the LGTBQIA community in Guatemala began gaining traction. The initiative called “Ley Para La Protección de la Vida y la Familiia” (Law for the Protection of Life and Family) was originally introduced in April 2017, and it is kept as a threat of sorts for political leverage. As of now, it has passed two readings in congress, but it still hasn’t been dismissed despite the fact that it limits the rights of people and criminalizes abortion in a country where the practice is already illegal. Some other points of the initiative make marriage between same-sex couples explicitly illegal, and forbid the possibility of a domestic partnership.

The most controversial provision of the initiative would protect discrimination against the LGTBQIA community under the law by stating that “every person has the right to freedom of conscience and speech, a right that implies that one is not obligated to accept as normal the conducts and practices of non-heterosexuals. No person could be prosecuted criminally by not accepting sexual diversity and/or gender ideology as normal, so long as they do not attempt against the life, integrity and dignity of people or groups that manifest conducts and practices that diverge from those in heterosexuality.”

The type of discrimination that would be allowed is not necessarily outspoken bigotry, but rather the slow drip of unjust or prejudicial treatment that affects the lives of those “living outside the norm” on a daily basis, something all-too-familiar for Lola Vásquez.

“I’m empowered and went to the IGSS, Guatemala’s Social Security, not too long ago because I suffered an injury on my finger,” Ms. Vásquez relates. “I have a legal name, I changed my name. I have a legal document that backs that, but on the part where it says ‘sex’ it still says I’m a male. The doctor, when he saw that, was resistant to treat me.”

“I was telling him that my name is Lola, but he was resisting by calling me Lalo,” she continues. “That’s the barrier he was putting on me: even though he saw my documents, my identity and saw that I am physically a woman, for him, my name is Lalo and he screamed it that way. So, imagine how, if those things that happen to me, an empowered woman who knows her rights and how to defend herself and is a spokesperson for many trans women… picture a girl from the countryside, how must she be treated?”

As right-wing populists continue rising to positions of political power and influence in Guatemala, the fight for gender equality seems to have stopped altogether, and the Law for Protection of Life and Family, also known as Law 5272, hangs over the LGTBQIA community as a major threat. Still, for most, the largest risk of being a trans woman in Guatemala for some lies on just being a female in the country with the second highest rate of gender inequality in Latin America.

“At the moment of my transition, when I became a woman, I degraded myself socially by becoming one,” says Ms. Vásquez. “I live through marginalization every day. I see it in the way people treat me, and when they refuse to accept the fact that I am a woman.”